What role do changes in the supply of banknotes play in contributing to a central bank's ability to carry out monetary policy? Put differently, to what degree does "printing," or creating new physical currency and issuing it into the economy, contribute to generating a central bank's desired inflation rate of 2-3%?

In a recent blog post at Econlog, Scott Sumner suggests that printing physical cash and "forcing" or "injecting" it into the economy has been an important part of central banks hitting their inflation targets, albeit less so now than in times past. I'm not so sure.

Having imbibed Scott's blog posts for more than a decade, I think I'm 99% on the same page as he is when it comes to thinking about monetary policy. We both agree that a central bank must either reduce the interest rate that it pays on the monetary base, or inject more monetary base into the economy, in order to push up prices. Using either of these two methods, the central bank sets off a hot potato effect in which a long chain of market participants do their best to unload their excess money balances, a process that only comes to an end when all prices have risen to a new and higher equilibrium such that no one feels any additional urge to spend away their extra money. Scott once described the hot potato effect as the the "sine qua non of monetary economics."

The monetary base is comprised of two central bank financial instruments: physical banknotes (a.k.a. cash) and digital clearing balances, sometimes known as reserves, a type of money used by banks.

Reading through Scott's post, I think the one spot where we may disagree is on the relative role played by the two types of base money in the hot potato process.

For my part, I don't think that cash has ever had much of a primary role to play in setting off a hot potato effect. All of the initial uumph necessary for driving prices towards target has typically been provided by reserves, either via a change in the interest rate on reserves or a change in their quantity. Once that initial uumph has been delivered, a whole host of other money types – physical currency, bank deposits, checks, money market funds, and PayPal balances – helps convey the forces originally unleashed by reserves to all corners of the economy.

An example of the hot potato effect in action may help illustrate.

Let's start with a central bank that needs to push inflation up to target. It reduces the interest rates on reserves. The first reaction to lower rates is a flight out of reserves into other assets, say shares.

As a result, share prices quickly rise. Those existing shareholders who realized their gains by selling at the new and higher price now find themselves with a hot potato on their hands; they have too many monetary balances in their possession and not enough non-monetary things.

Some of these ex-shareholders may choose to spend their excess deposits to go on, say, a vacation. As a result, airline ticket prices rise. Others transfer their extra money to their PayPal account in order to send it to friends and family, who may in turn make purchases, pushing up the prices of whatever they buy. Another group of ex-shareholders decides to buy used cars. They withdraw banknotes, their banks in turn asking the Fed to print new banknotes and ship them over. Used car prices rise.

The point is, the initial uumph is delivered by the change in reserves, and this gets conveyed to all prices by a daisy-chain of spenders offloading an array of different types of excess money.

In this story, note that cash isn't being actively "injected" into the economy by central banks, nor by commercial banks. Rather, people are choosing to draw cash out as their preferred method for getting rid of unwanted money, in response to a set of forces initiated by reserves. Reserves are the central bank's lever for change; cash is merely responsive.

Consider too that in a world where cash no longer exists, and has been replaced by digital payments options, monetary policy is still effective. In this world, the response to a reduction in the interest rate on reserves gets conducted to all the economy's nooks and crannies via non-cash types of monies, like fintech balances and bank deposits. (I'd be curious to hear if Scott is of the same opinion about monetary policy in a world without cash.)

Here's an interesting thought experiment. Would it be possible to redesign cash and reserves in such a way that cash takes over the initiatory role in monetary policy from reserves? That is, can we turn cash into the active part of the monetary base, the one that drives changes in monetary policy, and relegate reserves to the passive role?

One step we could take is to pay interest on cash. This may sound odd, but it's possible to do so by setting up a serial note lottery to pay, say, 3% per year to holders of cash. (I wrote about this idea here and here.) Simultaneously, reserves would be rendered less important by no longer paying interest on them.

Now when a central bank needs to raise consumer prices in order to hit its targets, it reduces the interest rate on cash from 3% to 2%. This ignites the hot potato process as the entire economy suddenly tries to offload its unwanted $20 and $100 bills, which at 2% just aren't as lucrative as before.

Another change we could enact would be to modify the mechanism by which central banks inject base money into the economy. As it stands now, central banks inject base money by purchasing assets with new reserves. Since reserves are digital, they are a lot more convenient for making billion dollar asset purchases than physical money. These extra reserves become hot potatoes in the hands of asset sellers, which sets off the process of price adjustments described in previous paragraphs. If central banks were to buy assets with cash rather than reserves, that would put cash in the driver's seat, albeit at the expense of convenience.

It's an interesting thought experiment, but in the end I don't think it's very helpful to get bogged down over which type of base money has more monetary significance. As Scott says, the key point is that the central bank controls the price level via its control over base money in general. They can raise prices by either adding to the supply of base money, or by reducing the demand for base money with a cut in the interest rate paid on reserves. "It's basic supply and demand, nothing more."

Wednesday, November 8, 2023

How would a cash-only central bank conduct monetary policy?

Friday, September 22, 2023

Coinbase: "What if we call them rewards instead of interest payments?"

Here's a question for you: which U.S. financial institutions are legally permitted to pay interest to retail customers?

We can get an answer by canvassing the range of entities currently offering interest-paying dollar accounts to U.S. retail customers. It pretty much boils down to two sorts of institutions:

- Banks

- SEC-regulated providers like money market funds.

There seem to be a few exceptions. Fintechs like PayPal and Wise are neither of the above, and yet they offer interest-yielding accounts to retail customers. But if you dig under the hood, they do so through a partnership with a bank, in Wise's case JP Morgan and in PayPal's case Synchrony Bank. (Back in the 2000s, PayPal used a money market mutual fund to pay interest). So we're back to banks and SEC-regulated entities.

And then you have Coinbase.

Coinbase will pay 5% APY to anyone who holds USD Coins (USDC), a dollar stablecoin, on its platform. (Coinbase co-created USDC with Circle, and shares in the revenues generated by the assets backing USD Coin.) The rate that Coinbase pays to its customers who hold USDC-denominated balances has steadily tracked the general rise in broader interest rates over the last year or so, rising from 0.15% to 1.5% in October 2022, then to 4% this June, 4.6% in August, and now 5%.

Coinbase isn't a bank, nor is it an SEC-approved money market mutual fund. And unlike Wise and PayPal, Coinbase's interest payments aren't powered under the hood by a bank.

So how does Coinbase pull this off?

In short, Coinbase seems to have seized on a third-path to paying interest. It cleverly describes the ability to receive interest as a "loyalty program", which puts it in the same bucket as Starbucks Rewards or Delta's air miles program. The program itself is dubbed USDC Rewards, and in its FAQ, customers are consistently described as "earning rewards" rather than "earning interest."

This strategy of describing what otherwise appears to be interest as rewards extends to Coinbase's financial accounting. The operating expenses that Coinbase incurs making payments on USDC balances held on its platform is categorized under sales and marketing, not interest expense.

Oddly, this key datapoint isn't disclosed in Coinbase's financial statements. Instead, we get this information from a conference call with analysts last year, in which the company's CFO described its reasoning for treating USDC payouts as rewards:

|

| Source: Coinbase Q4 2022 conference call |

The flow of "rewards" that Coinbase is currently paying out is quite substantial. Combing through its recent financials, Coinbase discloses in its shareholder letter that it had $1.8 billion of USDC on its platform at the end of Q2. Of that, $300 million is Coinbase's corporate holdings, as disclosed on its balance sheet. So that means customers have $1.5 billion worth of USDC-denominated balances on Coinbase's platform.

At a rewards rate of 5%, that works out to $75 million in annual marketing expenses. (Mind you, not everyone gets 5%. We know that MakerDAO, a decentralized bank, is only earning 3.5% on the $500 million worth of USDC it stashes at Coinbase). In any case, the point here is that the amounts being rewarded are not immaterial.

Interestingly, Coinbase does not pay rewards on regular dollar balances held on its platform. It only provides a reward on USDC-denominated balances. This gives rise to a yield differential that seems to have inspired a degree of migration among Coinbase's customer base from regular dollar balances to USDC balances.

For instance, at the end of Q1 2023, Coinbase held $5.4 billion in U.S. dollar balances, or what it calls customer custodial accounts or fiat balances. (See below). By Q2 2023 this had shrunk to $3.8 billion. Meanwhile, USDC-on-platform rose from $0.9 billion (see below) to $1.5 billion.

|

| Source: Coinbase Q1 2023 shareholder letter |

As the above screenshot shows, Coinbase has tried to encourage this migration by offering free conversions into USDC at a one-to-one rate. It has also extended the program to non-retail users like MakerDAO, although its non-retail posted rates are (oddly) much lower than its retail rates. Institutional customers usually get better rates than retail.

Incidentally, Coinbase isn't the only company to have approached MakerDAO to sign up for its fee-paying loyalty program. Gemini currently pays MakerDAO monthly payments to the tune of around $7 million a year, but calls them "marketing incentives." Paxos has floated the same idea, referring to the payments as "marketing fees" that would be linked to the going Federal Funds rate. The aversion to describing these payments as a form of interest is seemingly widespread.

There's two ways to look at Coinbase's USDC rewards program. The positive take is that in a world where financial institutions like Bank of America continue to screw their customers over by paying a lame 0.01% APY on deposits when the risk-free rate is 5.5%, Coinbase should be applauded for finding a way to offer its retail clientele 5%.

The less positive take is that USDC Rewards appear to be a form of regulatory arbitrage. Given that Coinbase uses terms like "APY" and "rate increase" to describe the program, it sure looks like it is trying to squeeze an interest-yielding financial product into a loyalty points framework, which is probably cheaper from a compliance perspective. If Coinbase was just selling coffee, and the rewards were linked to that product, then it might deserve the benefit of the doubt. But Coinbase describes itself as on a mission to "build an open financial system," which suggests that these aren't just loyalty points. They're a financial product. And financial products are generally held to strict regulatory standards in the name of protecting consumers.

We've already seen hints of regulatory push back against the rewards-not-interest gambit so popular with crypto companies. In the SEC's lawsuit against Binance, it named Binance's BUSD Rewards program as a key element in Binance's alleged effort to offer BUSD as a security, putting it in violation of Federal securities registration requirements. Like Coinbase's USDC Rewards program, BUSD Rewards offered payments to Binance customers who held BUSD-denominated balances at Binance. BUSD is a stablecoin that Binance offered in conjunction with Paxos.

Coinbase's lawyers seem to have anticipated this argument and have already prepared the legal groundwork to rebut it. The SEC sent a letter to Coinbase in 2021 that asked why USDC Rewards was not subject to SEC regulation. In its response, Coinbase had the following to say:

Now, I have no idea whether this is a good argument or not. Having observed securities law from afar over the last few years, I'm always a bit flummoxed by the degree of latitude it offers. It seems as if a good lawyer could convincingly argue why my Grandma's couch is a security, or that Microsoft shares aren't securities.Here's an interesting bit in which Coinbase goes into some detail why it believes USDC Rewards isn't a security: https://t.co/ZzXxvNkBsv I think it bears out the idea that once a firm starts offering a return, it risks straying into other regulatory frameworks. pic.twitter.com/DMC7l3Et33

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) August 4, 2022

If you think about it more abstractly though, loyalty points and interest are kind of the same thing, no? In an economic sense, they're both a way to share a piece of the company's revenue pie with customers. Viewed in that light, why shouldn't a program like USDC Rewards inherit the same legal status as Starbucks Rewards or air miles?

If Coinbase's effort to shape its USDC payouts as rewards ends up surviving, others will no doubt copy it. Wise and PayPal might very well stop using a bank intermediary to offer interest-paying accounts, setting up their own loyalty programs instead. A whole new range of investment opportunities marketed as loyalty programs might pop up, all to avoid regulatory requirements.

But it's possible to imagine the opposite, too. In a column for Atlantic, Ganesh Sitaraman recently described airlines as "financial institutions that happen to fly planes on the side." If loyalty points and interest are really just different names for the same economic phenomena, then maybe airline points, Starbucks Rewards, and USDC Rewards should all be flushed out of the loyalty program bucket and into stricter regulatory frameworks befitting financial institutions.

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

If Wise can pay interest, why can't USDC?

If Wise can offer interest and insurance to customers, why can't Circle (the issuer of USDC) do the same?

Wise and Circle are alike in a legal sense. Neither is a bank. Both are licensed as money transmitters. So why can one money transmitter offer a valuable set of services, but the other seemingly can't?

To be more accurate, it's not Wise itself that is offering these services. Wise is neither a bank nor a money market fund, so I'm pretty sure it is legally prevented from paying interest. And since it's not a bank, it can't be a member of FDIC. Rather, it is Wise's own bank, JP Morgan Chase, that is offering these services to Wise customers. Wise simply passes on the interest along with the insurance coverage.

So if Wise is just a feeder for JP Morgan, connecting its customer base to the bank, why can't Circle perform the same feeder role with its own bank, BNY Mellon, and USDC users?

I suspect one factor preventing this is the pseudonymity of stablecoins. There are many users of USDC, but Circle has only collected ID from a small fraction of them. A big chunk of USDC's pseudonymous user base is comprised of financial machines, or smart contracts, for which the concept of identification is meaningless. As for individuals or businesses who hold USDC, they may not be willing to, or can't, pass through a traditional verification process. Banks, however, have very strict onboarding rules. They must collect the ID of every single customer.

In short, it's probably quite tricky for Circle to feed USDC's mostly pseudonymous user base into an underlying bank in order to garner interest and insurance, at least much harder than it is for Wise to feed its base of known users into a bank.

It's possible that some USDC users might be willing to give up their ID in order to receive the interest and protection from Circle's bank. But that would interfere with the usefulness of USDC. One reason why USDC is popular is because it can be plugged into various pseudonymous financial machines (like Uniswap or Curve). If a user chooses to collect interest from an underlying bank, that means giving up the ability to put their USDC into these machines.

This may represent a permanent stablecoin tradeoff. Users of stablecoins such as USDC can get either native interest or no-ID services from financial machines, but they can't get both no-ID services and interest.

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

In which I catch Canadian banks paying more interest to customers than US banks do

|

| TD Bank operates on both sides of the border, yet pays more in interest on one side than the other. Source: TD |

Long-time readers will know that I like to muse on the competitiveness of U.S. and Canadian banking. In my last post on the topic, I was surprised to see how Bank of Montreal's net interest margins – a measure of how much a bank is squeezing out of its customers – were far lower in Canada than the U.S. The fact that Bank of Montreal is squeezing more out of Americans than Canadians suggests that competition is stiffer north of the border than south of it.

The idea that Canadian banking is more competitive than U.S. banking goes against what I'll call the "standard view." In short, this view is that while Canadian banks are safer and better-regulated than U.S. banks, this comes at a steep price. Up here in Canada, we've ended up with a few big oligopolistic institutions capable of charging exorbitant fees and paying unnaturally low interest rates, which hurts the consumer. Meanwhile, there are many more banks in the free-wheeling U.S., and while this makes for more bank failures and runs, the public benefits from lower fees and receives higher interest rates.

Anyways, I recently stumbled on another anecdotal piece of evidence that contradicts the standard view. TD Bank operates on two sides of the border, as the screenshot at the top of this blog post shows. Yet it pays depositors a different rate, depending on what country they live in:

Data like this is why I'm slowly starting to recant my view that America's 4000 or so banks create a healthier competitive environment than Canada's sleepy big-5 banking cartel. pic.twitter.com/QdcIS564li

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) March 31, 2023

As the chart shows, TD Bank consistently pays higher interest rates to its Canadian depositors. Why a persistent interest rate differential? You can't blame it on central bank policy rates being higher in Canada, since over much of this time frame policy rates were higher in the U.S. Is it possible that TD has to be more competitive in Canada in order to attract deposits?

An alternative explanation for the differential is that TD's deposits are of a different character in Canada. A big chunk of TD's Canadian deposits are fixed-term deposits that mature in 12-months or more, whereas its U.S. base of fixed-term deposits is typically shorter term, usually 3-12 months. Because it costs more in interest to convince depositors to stick around for longer periods of time, could it be that it is the difference in term – and not competition – that explains why TD's interest costs are so much higher in Canada?

Not quite. Even if we compare U.S. and Canadian interest rates for the same fixed term, Canadian banks still pay more interest to depositors. In Canada, the term of art for a fixed-term deposit is a guaranteed investment certificate, or GIC. In the U.S., it's a certificate of deposit, or CD. In the chart below, I've charted out the interest rate that Canadian banks pay for 1-year GICs compared to what U.S. banks pay for a 1-year CDs.

(For more on the data, see footnote*).

You can see that over the last few years, the big-6 Canadian banks have consistently paid more to 1-year fixed-term depositors than U.S. banks have. Again, you can't pin this on central bank policy rates being higher in Canada.

Canadian banks not only consistently pay more interest, they are also far more responsive to central bank policy rate increases. Both nations' central banks, the Fed and the Bank of Canada, began to hike rates in lockstep with each other beginning in March 2022, starting from close to 0% and rising to 4.75% and 4.5% respectively as of today. Yet Canadian banks began to pass-off these increases months before U.S. banks did. They have also done so far more completely; the 3.0% on a 1-year GIC is far closer to central bank policy rates of 4.5%-4.75% than the 1.5% on an equivalent CD. (And by the way, I wrote about sticky U.S. deposit rates last year.)

Could it be (gasp) that Canadian banks are more competitive?

Trust me, I don't like this conclusion. I quite enjoy thrashing Canadian banks for being noncompetitive. So if you have some good counter-evidence, please send it my way.

By the way, the above data confirms an anecdote from last year. I caught Canada's largest bank, Royal Bank, paying much more to Canadian depositors than U.S.'s largest bank, Chase, pays its American depositors:

It's very possible that the standard view is wrong, and the tug of war between Canada's 6 nationwide heavyweights result in a more competitive price than in the U.S. where – although there are more than 4,000 banks – they are often small and regional and lack the heft to engage in high calibre competition.Here's a riddle for folks who like to analyze the US and Canadian financial systems.

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) May 4, 2022

A 1-year t-bill yields 2% in 🍁 & 🇺🇸

Canada's biggest bank, Royal, pays 1.25% on a 1-year GIC. The US's biggest bank, Chase, offers just 0.05% on a 1-year CD.

What gives? Why such a huge gap?

If so, it appears you can have your cake and eat it too. Not only can a country have a safe and robust banking system, but that needn't come at the price of less competition.

*A note on my data sources for this chart. Canadian data comes from the Bank of Canada, which is compiled from posted interest rates offered by the six major chartered banks in Canada. The number is the statistical mode of the rates posted, which may explain the series' choppiness. U.S. data comes from FDIC, which compiles the data from S&P Capital IQ Pro and SNL Financial Data. Certificate of deposit rates represent an average of the $10,000 and $100,000 product tiers. Averaging across dozens or hundreds of banks would explain the smoothness of the U.S. series.

There are a number of complexities that are not explained by either data source. For instance, is the Bank of Canada's GIC data made up of non-redeemable GICs only, or do they include redeemable GICs, too? As for the U.S., banks like Chase offer a "relationship rate" to customers that far exceeds the non-relationship rate. Which rate is the FDIC collecting? I've suggested in my blog post that the difference in U.S. and Canadian 1-year fixed term deposits rates could be explained by competition, but it could also come down to data artifacts like these.

Tuesday, January 10, 2023

Why the steepest borrowing rate may be the best rate

(This isn't a piece of financial advice. It's more of a fun parable about interest rates.)

So here's an interesting financial riddle. Let's say I want to buy a used car for $1000.

First, I need a loan. Say that there are two floating rate loans available to me: one that currently costs 3.2% per year, and another that costs 2.3%. Logic dictates that I should take the cheaper 2.3% option, right? But I don't. Instead I take the more expensive one, figuring to myself that the expensive 3.2% loan is actually the cheaper loan.

Why on earth did I do that?

The rates in question are from the website for Aave, a tool for borrowing and lending cryptocurrencies, including stablecoins:

|

| The cost of borrowing two different stablecoins on Aave [source] |

If I borrow 1000 Tether stablecoins from Aave to fund my purchase of the $1000 car, it'll cost me 3.2%. But if I borrow 1000 USD Coins, it'll cost me just 2.3%. Those are floating rates, not fixed. (I could also borrow stablecoins on a fixed basis. A fixed-rate Tether loan would cost me 12.26% on Aave, a USD Coin loan 10.69%. Again, it's more expensive to borrow Tether.)

Why would I pay 3.2% to borrow one type of U.S. dollar, Tether, when I can get another type of U.S. dollar, USD Coin, at a cheaper rate? I mean, they're both dollars, right? They each do same thing; that is, they both provide me with the means to buy a $1000 car.

To see why I might prefer the more expensive Tether loan, we need to understand why the rates on Tether and USD Coin differ:

If I borrow 1000 stablecoins to buy a $1000 car, eventually I'll have to buy those 1000 stablecoins back in order to repay my loan. Wouldn't it be nice if, in the interim, the stablecoin I've borrowed loses its peg and falls in value? Because if it were to do so, I'd be able to buy back the 1000 stablecoins on the cheap (say for $400 or $500), pay back my 1000 stablecoin loan, and keep the $1000 car.

In short, I'd be getting a $1000 automobile for just $400-$500 plus interest.

By contrast, if I were to borrow a more robust stablecoin in order to purchase the car, then that'd reduce the odds of its price being weak when it comes time to repay my loan, thus making the entire transaction more expensive to me.

A $1000 car would cost me... $1000 plus interest.

We can imagine that all potential borrowers are perusing Aave's loan list with that exact same thought in mind. Jack wants to finance a house for $250,000 by getting a stablecoin loan on Aave. Jane wants to borrow $100 in stablecoins on Aave to pay off her credit card debt. All three of us would really, really, really, like to borrow a stablecoin that fails, reducing the net cost of our purchase. So we all do our respective research and select what we believe to be the stablecoin with the worst prospects, the one most likely to be worth just 40 or 50 cents when it comes time for us to repay our debt.

The competition between the three of us to borrow the worst stablecoin will cause borrowing rates for the worst stablecoins to rise. Conversely, borrowing rates on the stablecoins with the best prospects will fall.

And that's what I suspect is happening on Aave. Tether is seen as the riskier stablecoin. And so from the perspective of the borrowing public, a Tether loan is superior to a USD Coin loan. Jack, Jill, and myself are all scrambling for the privilege of borrowing Tether, in the process pushing the cost of borrowing Tether 0.9% above the cost of borrowing USD Coin.

Now we can get back to the original riddle. Even though the rate to borrow Tether is higher than the rate to borrow USD Coin, it may be worthwhile for me to go with the a Tether loan if I think that the odds of Tether failing justify the higher financing cost.

We can even go a bit further and say that the 0.9% premium on a Tether loan is the market's best estimate of the odds of Tether losing its peg relative to USD Coin losing its peg. So for all those would-be stablecoin analysts out there, keep your eye on Aave's USD Coin-Tether spread. It's a good indicator of stablecoin risk.

P.S: The difference between the cost of borrowing Tether and USD Coin could also be due to the liquidity premium on Tether being larger than the liquidity premium on USD Coin. I'm not going to get into that possibility in this post, but if you're curious ask me about it in the comments.

P.P.S: Does this same logic apply to borrowing from banks? Would I rather borrow from a bank that's about to fail rather than a solid respectable bank?

P.P.P.S: Some Dune dashboards tracking he Tether-to-USD rate premium: here and here.

Monday, December 12, 2022

Are U.S. banks more competitive than Canadian banks?

Over the years I've had a lot of connections to the Bank of Montreal. I'm a disgruntled ex-customer, a fairly happy shareholder, and a former employee. I stopped being a customer after the Bank of Montreal began charging me monthly fees in the middle of the pandemic without telling me, and I didn't notice for over a year. They refused to refund the fees, so I walked.

In any case, given my multiple interactions with the Bank of Montreal, I try to keep tabs on what it is doing. I was glancing through the bank's 2022 annual financial statement and stumbled on the following notable table:

|

| Source: BMO. P&C refers to personal & commercial banking |

The bits that struck me are in yellow. Bank of Montreal's net interest margin is much higher in the U.S. than Canada. By way of background, Bank of Montreal is fairly unique in that it operates as a sizable commercial bank on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border. So its data, including its margins, provides some interesting insights into the fundamental differences between U.S. and Canadian banking.

Net interest margin is a measure of how much a bank is squeezing out of its customers. To calculate it, start by counting up how much money a bank makes in interest on its loans. Then subtract from that its interest costs: all the money it pays out to depositors in the form of interest. That difference is the bank's net interest. Divide net interest by all of the money it makes on its loans to get net interest margin.

Banks want higher margins. Their customers don't. The higher the net interest margin, after all, the more interest the bank is extracting from its customers.

In Bank of Montreal's case, its margin in the fourth quarter is 3.88% in the U.S. and 2.66% in Canada. So for every $100 it lent, the bank collected net interest of $3.88 in the U.S. but just $2.66 north of the border. In short, Bank of Montreal was much better at squeezing Americans than Canadians in 2022. That difference in margins doesn't sound like much, but repeated over billions of dollars it comes to quite a gap.

This isn't a fleeting phenomenon. I glanced over the last 10-years of Bank of Montreal financial data, and its U.S. net interest margin has been consistently superior to its Canadian margin over that entire period.

This goes against my long-standing stereotype of Canadian vs U.S. banking, which goes a bit like this:

I've always thought that it was better to be a U.S. banking customer than a Canadian one. Canada once had a fairly vibrant banking sector, but after many waves of mergers and acquisitions it has consolidated to the point that we've really only got five big bank. Everyone refers to them as an oligopoly. Everyone. I recall that even the Bank of Montreal's in-house bank equity analyst routinely referred to Canada's big 5 as an oligopoly in his research reports.

To make matters worse, Canada prevents foreign competitors from entering and stirring up the pot.

But America is huge and thus capable of supporting a much richer range of banks. For instance, the big 5 Canadian banks hold assets equal to 2.5 times Canada’s gross domestic product, but the assets of the five largest U.S. banks amount to just 0.4 times of that country’s GDP. See the chart below:

This chart from @jason_kirby really gives a feel for how much more concentrated Canadian banking is relative to the U.S.

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) April 28, 2022

via https://t.co/L4cosgydaN pic.twitter.com/A872GimuI3

This lack of concentration means that U.S. banks don't have the same oligopolistic stranglehold over Americans that Canadian banks do.

On top of that, U.S. commercial culture is more cutthroat than Canada. Whereas foreign banks are locked out of Canada, they can freely enter the U.S. market. And so I saw the U.S. as an arena for ferocious bank competition, with customers benefiting in the form of better services and higher interest rates. Meanwhile, we Canadians are getting stiffed by our banks.

But after looking Bank of Montreal's net interest margins, I'm not so sure about my stereotype. A lower net interest margin in Canada means that the bank is extracting a smaller pound of flesh from its Canadian customers, which suggests more banking competition up here, not less.

Incidentally, net interest margin doesn't include those pesky user fees we all hate, or what Bank of Montreal calls non-interest revenue. And we know that the Bank of Montreal ruthlessly skins its customers for fees; after all, that's why I closed my account. However, even after adding Bank of Montreal's non-interest revenues to its net interest income on both sides of the border, its Canadian banking business still only sports a margin of 3.5% in fiscal year 2022 compared to 4.5% for its American business.

That is, even after accounting for pesky user fees, Bank of Montreal is still gouging its American customers more than it gouges its Canadian ones.

Admittedly, Bank of Montreal provides just a single data point. So I cast around for more data, and stumbled upon a database called Bankscope, hosted on the Federal Reserve's FRED. Bankscope is a popular source of bank balance sheet information among banking economists.

Here is what U.S. and Canadian net interest margins from Bankscope look like:

|

| Chart source: FRED |

It confirms my Bank of Montreal anecdote. Going back to 2000, banking net interest margins in the U.S. have been consistently higher than in Canada, and by quite a large amount.

To sum up, given the preceding data I may have to revamp my conceptions of Canadian and U.S. banking. It's true that we have an incredibly concentrated banking sector up here in Canada, with the big 5 controlling an outsized chunk of the market. Paradoxically, this "oligopoly" doesn't translate into higher net interest margins for Canadian banks. Margins are actually more elevated in the the hotbed of capitalism, the U.S., even though its banks are far more diffused. This margin difference suggests that competition among banks is more strident north of the border than south of it.

In short, although the bastards at the Bank of Montreal skinned me for a bunch of fees during the pandemic, the bigger picture is that it's better to be a customer of a Canadian bank than a U.S. one.

Thursday, October 13, 2022

Stablecoins, meet 3% interest rates

The global rise in interest rates is finally beginning to percolate into the stablecoin sector. One of the effects of this rise is that centralized stablecoins like USD Coin and Gemini Dollar, which by default pay 0% to holders, are introducing backdoor routes for paying interest to large customers. (See my tweets here and here).

In the case of USD Coin, Coinbase refers to interest as a "reward." Gemini calls it a "marketing incentive." But less face it: they're really just interest payments.

The links I provide are the only public evidence of stablecoins doling out interest, but you can be sure that behind closed doors, large issuers like Circle/Coinbase, Gemini, and others are offering their largest customers -- in particular exchanges like Binance and Kraken -- the same deals.

Stablecoin issuers are offering interest to select customers because of the inexorable pressure of competition. After hovering near 0% for much of the last decade (see chart above), interest rates have ramped up to 3% in just a few months. Issuers hold assets to back the stablecoins that they've put into circulation, and now these previously barren assets are yielding 3%. That means a literal payday for these issuers. In the first quarter of 2022, for instance, Circle (the issuer of USD Coin) collected $19 million in interest income after making just $7 million the quarter before. In the second quarter of 2022, interest income jumped to $81 million. I suspect the third quarter tally will come in well above $150 million.

However, if they don't share at least some of this juicy reward, issuers risk having their customers flee to alternatives that do offer interest, like Treasury bills or corporate deposit accounts. And then the amount of stablecoins in circulation will shrink, eating into issuers' revenues.

And thus, we get to a world where Gemini is promising incentives and Coinbase rewards.

Alas, while large stablecoin holders may be benefiting from this trend, small holders of stablecoins are being ignored. They don't get to share in these sweet flows of interest income. Even folks with old-school U.S. savings accounts are being paid 0.17%!

Small stablecoin holders need to unite. By working together through a StablecoinDAO, their bargaining power vis-a-vis the big stablecoin issuers improves. They may be able to negotiate the same interest payments from Circle and other issuers that large stablecoin customers are getting.

For a good example of strength in numbers, take a look at the phenomenon of high-interest savings ETFs in Canada. Corporate customers of Canadian banks get far better interest rates on chequing deposits than retail customers do. A high-interest savings ETF manager bridges this divide. They collect money from retail customers, invest the proceeds in banks at the corporate rate, and then share the superior return with thousands of retail ETF unit holders.

StablecoinDAO would have the authority to swap one underlying stablecoin out with a new one. That potential threat would give the DAO the necessary leverage to negotiate interest payments. "Hey Circle, if you don't pay us 1% then we're going to shift the DAO's holdings over to Binance USD, your competitor." As a nuclear option, the DAO could threaten to buy short-term government debt.

The interest that the DAO receives would be funneled back to UniteUSD holders.

In sum, that's how interest rates finally filter through to small stablecoin owners.

A few random afterthoughts about stablecoins and interest payments, in no particular order:

* A version of StablecoinDAO may already exist... in the form of MakerDAO, a decentralized-ish bank that issues Dai stablecoins. Think of MakerDAO as an organizing device for small stablecoin customers to extract interest from stablecoin issuers. These small holders deposit their stablecoins (USD Coin, USDP, etc) into MakerDAO smart contracts and receive Dai stablecoins in return, which are convertible to any of these underlying stablecoins on a 1:1 basis. MakerDAO negotiates with issuers for interest payments, sluicing this interest back to Dai owners.

* Some tricky regulatory issues arise when retail customers are promised a return. If StablecoinDAO were to pay interest on UniteUSD, then UniteUSD might be deemed to be a security, and thus StablecoinDAO would have to register with a securities agency. This could doom StablecoinDAO, or at least make things very difficult for it. (Remember, when PayPal used to pay interest to customers? It did through an SEC-registered money market mutual fund.)

* StablecoinDAO would become a stablecoin black hole: all other stablecoins would quickly get sucked up into it. Why? In a world where USD Coin and USDP can only pay 0% to small stablecoin holders, but depositing said coins into StablecoinDAO means earning 2%, then every small holder will deposit their funds into StablecoinDAO. The DAO would inhale the big stablecoins -- USD Coin, Binance USD, Tether, etc -- right out of circulation, leaving UniteUSD as the dominant stablecoin.

* As competition forces large issuers to share the interest they earn, this will have implications for the finances of those very issuers. Circle, the issuer of USD Coin, envisions being profitable in 2023, as the table below illustrates:

|

| Source: Circle Q2 2022 financials [link] |

A big part of Circle's estimates are based on higher flows of interest from the assets that it holds to back USD Coin. What this table isn't accounting for is the concurrent pressure to share interest income with USD Coin holders, both large and small ones, which threatens Circle's 2023 projections.

Tuesday, April 26, 2022

Where are the customers' rate increases?

U.S. banks are at it again. Inflation is at its highest level in decades. At the same time, interest rates on deposits at the Fed, Treasury bills, bonds and mortgages are rising rapidly to compensate. Yet banks are still in a holding pattern when it comes to the interest rates they pay to customers on savings accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), and interest-checking accounts.

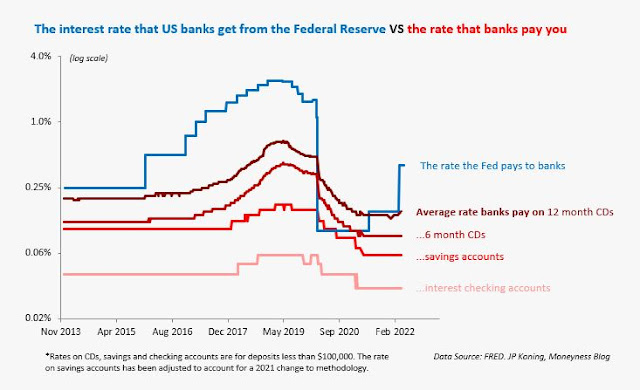

Here's the chart, which uses FDIC data from FRED. Note how customer deposit rates (in red) have hardly budged, despite the Fed beginning to raise rates last summer. This same sluggishness also occurred in 2015, the last time the Fed began to

hike rates. Banks didn't boost savings accounts rates till two years later, in 2017!

Historically, rates on CDs seem a little more responsive. But they're still sluggish. The average 6-month CD still only yields a scrawny 0.09%, whereas the yield on a 6-month Treasury bill is now at 1.4%.

This stickiness wouldn't be such a big deal if banks were also slow to reduce interest rates on customers' accounts – win some, lose some, right? But take a look at what happened when the Fed began to cut rates in mid-2019. Banks didn't hold off. They immediately started to pass lower rates on to their customers, and only became more aggressive when COVID hit in March 2020.

This observation isn't something that economists have ignored. In a paper entitled "Sticky Deposits", Federal Reserve economists John Driscoll & Ruth Judson found that rates are "downwards-flexible and upwards-sticky." This stickiness has consequences for regular Americans. If rate stickiness didn't exist, the authors estimate that U.S. depositors would have received as much as $100 billion more in interest per year!

Monday, June 29, 2020

Is fiat money to blame for the Iraq war, police brutality, and the war on drugs?

The military-industrial complex that deliberately creates wars is financed by inflationary State fiat currencies.— Pierre Rochard (@pierre_rochard) January 8, 2020

The rough idea behind this family of memes is that the Federal Reserve, the world's largest producer of "fiat" money (i.e. irredeemable banknotes), is responsible for financing all sorts of examples of government over-reach, say foreign invasions, police brutality, and the twin wars on terrorism and drugs. It does so by producing seigniorage, or profit, which it passes on to the state. Replace fiat-issuing central banks like the Fed with bitcoin or a gold standard, and seigniorage would cease to exist. With the government's purse strings having been cut, a relatively peaceful society would be the result.

This meme's premise is wrong. In practice, central bank seigniorage in both the U.S. and other developed nations is a very small part of overall government revenues. And so even if fiat money were to be displaced, say by bitcoin or a gold standard, it wouldn't change the state's ability to fund the war on drugs and adventures in the Middle East.

Let's look at the U.S. Below are two charts showing how much income the Federal Reserve has contributed to the Federal government's overall receipts going back to 1950. (Beware. One chart relies on a regular axis, another a logarithmic axis. But they use the same data). The Fed's contribution has been steadily growing over time. In 2019, it sent about $53 billion to the Federal government.

You may be wondering how the Fed generated $53 billion in profit, or seigniorage, in 2019. Most of this income comes from issuing banknotes, or cash. For each $1 in banknotes that it issues to the public, the Fed holds an associated $1 of bonds in its vault. These bond have typically yielded 3-4% in interest. But the Fed only pays 0% interest to the owners of its banknotes. Which means that it gets to keep the entire 3-4% flow of bond interest for itself. It forwards this income to the Federal government at the end of the year.*

Seigniorage tends to grow over time. (But not always. Below I'll show how Sweden's seigniorage has been shrinking). The larger the quantity of banknotes that the public wants to own, the more interest-yielding bonds the Fed gets to hold, which means more seigniorage. In general, banknote demand increases with economic and population growth.

Interest rates are another big driver of seigniorage. If bond interest rates rise from 4% to 8%, the Fed earns more on the bonds it owns in its vault. Banknotes continue to yield 0% throughout, so the Fed keeps the entire windfall for itself (and ultimately for the Federal government).

By the way, a big driver of nominal interest rates is inflation. If inflation is expected to double, then bond owners will require twice the interest to compensate them for inflation risk. So inflation boosts seigniorage (because it boosts the interest rate that the Fed earns on the bonds in its vaults), and deflation hurts seigniorage (because it reduces interest rates). In the chart above, the one with the logarithmic axis, you can see how the Fed's seigniorage increased during the inflationary 1970s. It flatlined from the mid-1980s to the early early 2000s, which coincides with inflation subsiding.

US seigniorage is relatively small. In addition to enjoying revenues from the Federal Reserve, the U.S. Federal government also gets money from individual and corporate income taxes, social insurance and retirement receipts, excise taxes, duties, and more. Below I've charted the relative sizes of these contributions.

As you can see, the Fed's contribution (the grey line) is a rounding error.

Below is a chart showing what percentage of total government revenue is derived from the Fed.

In 2019 the Fed contributed just 1.5% of total U.S. Federal government receipts. This contribution has hovered between 1% to 3% over the last four decades. So the meme that fiat money abetted the Iraq War, the expansion of the police state, or the U.S.'s military industrial complex is mostly hyperbole.

What about other developed nations?

The Bank of Canada provided $1.2 billion in earnings to the Canadian Federal government in 2018. But the Federal government took in $313 billion in revenues that year, which means that the Bank contributed a tiny 0.4% fraction of total revenues. The reason for the big gap between the Bank of Canada's tiny 0.4% contribution and the Fed's 1.5% contribution is the global popularity of the US$100 bill. Canadian cash doesn't enjoy a big foreign market.

I mentioned Sweden earlier. Below is a chart of seigniorage earned by the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank.

Sweden's central bank, @riksbanken, used to earn a handsome profit by issuing banknotes, ie seigniorage.— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) August 28, 2019

With cash usage wilting & interest rates hitting zero, seigniorage has collapsed. If these trends continue, issuing cash could become a financial burden for the Riksbank. pic.twitter.com/LCYOJ3q8dZ

Sweden is one of the only countries in the world where banknote ownership has been falling. This de-cashification is compounded by interest rates that have fallen close to 0%. Which means that the Riksbank's bond portfolio isn't earning as much as it used to. This combination has just decimated the Riksbank's seigniorage. In 2018 its seigniorage amounted to a paltry SEK 267 million (US$29 million). This is just 0.00003% of all Swedish central government receipts.

So in sum, central banks in places like the US, Canada, and Sweden are not a big source of government funding. If you want to stop governments from engaging in bad policies like the war on terror, the war on drugs, and foreign meddling, you've got to work within the system. Vote, send letters, go to protests. Sorry, but buying bitcoin or gold in the hope that it somehow defunds these activities by displacing the Fed is not a legitimate form of protest. It's a cop-out.

P.S. By the way, I am not saying that control of the nation's money supply hasn't been used to finance wars in the past. Obviously it has. Greenbacks helped pay for the Union's war against the Confederates. Henry VIII paid for his wars by dramatically reducing the supply of silver in the English coinage.

*The Fed enjoyed a big spike in seigniorage after the 2008 credit crisis. This is because it issued a bunch of deposits to bank (known as reserves) via quantitative easing. The Fed only had to pay 0.25% interest on these reserves, but the bonds that backed them were earning 2-3%. This QE-related income has declined as the Fed has unwound QE (since reversed) and long-term interest rates have declined.

Wednesday, June 24, 2020

Banks are slow to increase rates on savings accounts, but quick to reduce them

|

| Chase Sunset & Vine, 2012. Painting by Alex Schaefer |

There is a fundamental asymmetry to banking. Banks don't like to share higher interest rates with their customers who have checking and savings accounts. But they are quick to pass off lower interest rates to us.

This asymmetry is good for bank shareholders, but bad for customers.

To illustrate this asymmetry, I'll start by showing how banks modified interest rates on savings and checking accounts as the Federal Reserve, the U.S.'s central bank, went through a long period of hiking interest rates from 2015 to 2019.

The Federal Reserve's first rate increase (from 0.25% to 0.5%) was in December 2015. It increased rates once more in 2016 and three times in 2017. But the interest rate on the average U.S. savings account and interest checking account didn't start to rise till spring 2018, two and a half years after the Fed's first rate hike.

This irked me and I tweeted about it over a year ago:

Any day now, banks.— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) May 17, 2019

I understand why the rate that banks pay to savers is below the rate that the Fed pays banks (they need to cover costs). But I find it kind of shocking that banks don't match the pace of Fed rate increases. Shouldn't savings accounts by yielding ~1% by now? pic.twitter.com/ctK35xkvmc

If you're like me, you'd assume some sort of direct linkage between: 1) the interest rate that the Federal Reserve pays its customers (i.e. banks) and 2) the rate that these same banks pay their customers, you and me. Just like we have a checking account at a bank, banks maintain checking accounts at the Federal Reserve. They earn interest on balances held in those accounts. This rate is known as the Fed's interest rate on reserves, or IOR. As the Fed increases the interest rate that it pays on these checking accounts, the banks earn more from the Fed. But for some reason the banks are slow in passing these earnings on to the public.

Although the delay in pass-through irked me, I didn't take it too seriously, figuring it was due to some sort of institutional inertia. Banks are slow monolithic beasts. If they're slow to increase rates, at least they're slow to chop them, too, right? So on net, we customers aren't any worse off over the full economic cycle.

But if banks are slow to increase rates, is it indeed the case that they are also slow to reduce rates? Well, the results are in. The Fed began to cut rates in mid-2019, just around the time of my initial tweet. There were another few cuts in the latter half of 2019. Then COVID-19 hit in March, and the Fed rapidly ratcheted the rate it pay banks down from 1.6% to 0.1%. Banks went from earning around $38 billion in interest on their checking accounts at the Fed (in fiscal year 2018) to almost nothing.

If banks are generally lethargically about passing on rate changes to their customers, it should have taken them three or four years to reduce rates on savings and checking accounts back to where they had started. Nope. In just a month or two, the banks obliterated all the interest rate gains that customers with savings account had enjoyed since 2018:

Thanks for nothing, banks.— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) June 3, 2020

From 2016 to 2019, U.S. banks slowly passed on Fed rate increases to their customers. Look how fast they passed on Fed rate reductions in 2020! pic.twitter.com/jt8hHgvL7F

So no, banks aren't lethargic beasts that are universally slow to change interest rates enjoyed by savers. They seem to have a strategy of increasing rates slowly, and then reducing them rapidly. Assholes.

Note that the savings rate I am using is from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation's website. FDIC takes the simple average of rates paid by all insured depository institutions and branches for which data are available.

By the way, this data probably doesn't represent the experience of the minority of financial sticklers who make an effort to locate high-interest rate savings accounts at online-only banks.

This asymmetry is not a new phenomenon. In "Sticky Deposits", Federal Reserve economists John Driscoll & Ruth Judson found that rates are "downwards-flexible and upwards-sticky."

More specifically, the authors used proprietary data from 1997 to 2007 to show that interest rates on bank accounts and other retail deposits adjust about twice as frequently during periods of falling Fed interest rates as they do in rising ones. They estimate that this sluggish pass-through from rising Fed rates to customer rates costs American consumers around $100 billion per year!

My favorite chart from Driscoll & Judson is below:

|

| Source: Judson & Driscoll |

At left, we see the number of weeks it takes for banks to decrease the rate on interest checking accounts in response to a cut in the Fed's interest rate. At right we see the converse, how long it takes increase rates in response to higher Fed rates. Decreases tend to happen quickly (the purple bars in the left chart congregate closer to zero weeks) whereas increases are slow (the purple bars in the right chart congregate close to 100 weeks).

More specifically, during Fed easing cycles, checking deposit rates are updated on average every 22 weeks, but during tightening cycles it takes an average of 50 weeks.

So what explains this asymmetry? A lack of competition perhaps? If I had to guess, I'd say low financial education and dearth of customer attention. Banks can afford to be assholes because most customers either don't understand what is happening, or don't notice.

If the banks are taking advantage of their customers' ignorance and inattention to the tune of $100 billion per year, should something be done?

One option would be to provide a government savings option that 'corrects' for this asymmetry. Like digital savings bonds. Or maybe a government prepaid debit card with a built-in savings account. These cards would offer an interest rate that is linked to the Federal Reserve's interest rate, but only available to those below a certain income ceiling.

Or what about setting statutory minimum interest rates on savings accounts? In Brazil, for instance, banks are obligated to link the rate they pay on savings accounts to the central bank's interest rate:

In the US, interest rates on savings accounts are minuscule. This would be illegal in Brazil, where banks must set rates using a formula linked to SELIC, the central bank's policy rate: https://t.co/3bupDm4L8f— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) May 17, 2019

SELIC is 6.5%. Savings accounts must yield 70% of that, or 4.55%. pic.twitter.com/EPkkbROQvY

Or maybe it starts with education. As part of its new financial literacy drive, Ontario will teach children how to identify Canadian coins and bills and compare their values in Grade 1, saving and spending from Grade 4, how to budget starting in Grade 5, and financial planning starting in Grade 6. If the result is a more savvy population, banks may face more pressure to pass on higher interest rates.

Or maybe nothing. In which case one hopes that over time the combination of better financial technology, branchless banking, and competition from Silicon Valley will eventually result in better pass-through and more symmetry in interest rates.

Friday, November 22, 2019

Notes from an inter-planetary monetary anthropologist

My work as an inter-planetary monetary anthropologist has brought me to dozens of different planets to study their monetary systems. The monetary system of the most recent planet that I visited, the planet of Zed in the Xv2 galaxy, falls into the same classification as the systems on Vigil X and Earth (which I last visited in 1998 and, according to other anthropologists, hasn't changed much).

As on Earth, markets on Zed tend to lie towards the free end of the spectrum. Zedians can own property. And property rights are enforced. Zedians often put their savings in institutions much like banks and earn interest. Banks in turn lend to individuals and business.

However, one of the oddities of the planet of Zed is that its inhabitants universally adhere to an economic religion, Zodlism. One of the strictures of Zodlism is that all monetary instruments must yield at least 2% interest. Even a transactional account, say like Earth's checking accounts, must offer the account holder a minimum 2% per annum.

This requirement is based on the Zodlist stricture that anyone who is temporarily deprived of an object to the benefit of someone else deserves a minimum reward for their sacrifice. Banks that fail to meet the 2% requirement risk censure from the planetary religious organism, the Zodl Council, and ostracism by customers. (For a full account of Zodlist economic doctrine, see Smith & Elf33, pgs 450-512).

Interestingly, banknotes (which on Zed are issued by all sorts of different institutions and individuals, unlike Earth which confines that role to central banks) also pay 2% interest. Each note has a sensor in it that records how much interest the note has accrued. Any Zedian can access unpaid balances by uploading them to their account or claiming them at a trading post when making a purchase. Zed is a little further ahead than Earth in this respect, which still hasn't bothered digitizing its banknotes.

While I was visiting Zed, the planet's economy was facing an unprecedented economic slowdown. With optimism sapped, borrowing on Zed had been plummeting. Zedians were simply too afraid about the future to take out loans to fund business expansion or enlarge their underground shelters. In response to this decline in loan demand, bankers had been trying to make loans more attractive to the Zedian public by pushing lending rates ever closer towards 2%.

Bankers have even been entertaining the revolutionary idea of lending at rates below 2%, say to 1.5%.

This would leave Zedian banks and note issuers in an odd position. If they only earn 1.5% from borrowers while paying depositors the obligated 2%, banks would be effectively paying out more than they receive in interest. But this is the opposite of what banks are supposed to do! They would soon go out of business. (Any Zedian could make a risk-free profit by taking out a bank loan at 1.5% and depositing those funds at the bank to earn 2%.)

Pressure is building on Zed's religious leaders to alter the 2% rule. Some moderate Zodlists have proposed that a ceremonial 2% rate continue to be paid to depositors and banknote owners, but a fee be levied to claw back a part of the interest. So that if someone is paid 2 Zed in interest, the bank or banknote issuer will take back about half that in fees, ie. 1 Zed. This would allow issuers to 'synthesize' an interest rate of 1% while still conforming to the letter of Zodlism. Once this change is implemented, banks would be able to safely lend at 1.5% or so.

These pragmatists argue that at 2% per annum, borrowing it just too expensive for most people. The planet requires an interest rate of 1.5% if lenders are to be successful in luring the public back into taking on loans. They further argue that when would-be borrowers are priced out of the market, the downturn is exacerbated and prolonged. But strict Zodlists refuse to budge. The idea of earning just 1% on banknotes appalls them. "It's unnatural!" they cry.

The debate certainly reminds me of my time on Earth. Historically, Earth's religions also set limits on interest rates. But whereas Zodlism dictates a minimum interest rate on deposits, Earth tended to set a maximum rate on loans. These rules were referred to as usury laws. Perhaps Zed could learn from its distant planet, since Earth (or at least parts of it) saw it fit to end usury laws long ago. I feel like this softening is likely to happen. In their survey of 450 planetary monetary systems, LeGuin & Xsszym find that law and religious practices tend to bend to planetary economic exigencies.

Unfortunately, I never saw the resolution to Zed's 2% debate. My ship had arrived to take me to the next planet. Perhaps I can come back one day to see if Zedians have solved the problem.

Addendum: In 2019 I returned for a quick return visit to Earth. Who would have guessed, but they are facing many of the same problems that Zed is experiencing!

Saturday, August 31, 2019

Why the discrepancy?

Today's post explores what goes into determining interest rates, not blockchain stuff. So for those who don't follow the blockchain world, let me get you up to speed by decoding some of the technical-ese in Buterin's tweet.Lending DAI to Compound offers 11.5% annual interest. US 10 year treasuries offer 1.5%. Why the discrepancy?— Vitalik Non-giver of Ether (@VitalikButerin) August 23, 2019

DAI is a version of the U.S. dollar. There are many versions of the dollar. The Fed issues both a paper and an electronic version, Wells Fargo issues its own account-based version, and PayPal does too. But whereas Wells Fargo and PayPal dollars are digital entries in company databases, and Fed paper dollars are circulating bearer notes, DAI is encoded on the Ethereum blockchain.

Buterin points out that DAI owners can lend out their U.S. dollar lookalikes on Compound, a lending protocol based on Ethereum, for 11.5%. That's a fabulous interest rate, especially when traditional dollar owner can only lend their dollars out to the government—the U.S. Treasury—at a rate of 1.5%.

Why this difference, asks Buterin?

Interest rates are a lot of fun to puzzle through. I had to think this one over for a bit—so let's slowly work through some of the factors at play.

Let's begin by flipping Buterin's question around. When the U.S. Treasury borrows from the public, the bonds it issues are promises to pay back regular dollars (i.e. Federal Reserve dollars). But what if the U.S. Treasury decided to borrow DAI by issuing bonds promising to repay in DAI? What would the interest rate on these Treasury DAI bonds be? Would it be 11.5% or 1.5%? Perhaps somewhere in between?

Credit risk

First, there's the question of credit risk. The U.S. Treasury is a very reliable debtor. It won't welch. If it issues both types of bonds, it'll be just as likely to repay its DAI bond as it will its regular dollar bond. Since the market already requires 1.5% from the Treasury to compensate it for credit risk (and a few other risks), the Treasury's DAI bonds should probably yield 1.5% too. (I'll modify this later as I add some more layers).

Now let's look at Compound. A DAI loan made on Compound (for simplicity let's just call it a Compound DAI bond) is surely much riskier than our hypothetical Treasury DAI bond. Compound is a blockchain experiment. It could malfunction due to buggy code. Maybe every single Compound borrower goes bust. To compensate for this risk, a prospective bond buyer will require a higher return from Compound DAI bonds than they will U.S. Treasury DAI bonds.

So Compound credit risk (Buterin's third option) probably explains a big chunk of the huge gap between the 11.5% interest rate on Compound DAI bonds and our hypothetical 1.5% interest rate on the U.S. Treasury's DAI bonds. But not all of it.

Collapse risk

Buterin mentions a second risk: the chance that DAI, the entity that creates blockchain dollars, collapses. Like Compound, DAI is a new monetary experiment. The code could be buggy. It might get hacked. By comparison, conventional dollar issuers—say Wells Fargo or PayPal—are far less likely to malfunction.

How does DAI collapse risk get built into the price of a hypothetical Treasury DAI bonds

The average market participant (I'm not talking about crypto fans here, but large & smart institutional actors) should be genuinely worried about purchasing a Treasury DAI bond—not so much because the Treasury is unlikely to pay it back—but because the DAI tokens that the Treasury ends up repaying could, in the even of DAI breaking, be worth 99% less than their original value. Average bond buyers will expect some compensation for bearing this risk. How much? Say 5.5% (I'm just guessing here).

Earlier I said that a Treasury DAI bond would yield 1.5%. But if we add 5.5% worth of failure risk to 1.5% in basic risk, a Treasury DAI bond should yield 7.0% before the average investor is going to hold it.

Now let's go back and look at a Compound DAI bond. As Buterin pointed out, they yield 11.5%, which is much higher than the 7.0% yield on our hypothetical Treasury DAI bond. We've already assumed that DAI collapse risk works out to 5.5%. If we subtract collapse risk from a Compound DAI bond's 11.5% yield, the remaining 6% is accounted for by risks such as Compound failing (11.5% - 5.5%). Put differently, investors in Compound DAI bonds will require 5.5% and 6.0% to compensate for collapse risk and credit risk respectively, for a total of 11.5%. Again, these are hypothetical numbers. But they help us puzzle things out.

Two different blockchain dollars: USDC vs DAI

Interestingly, Compound doesn't just facilitate DAI loans. It also expedites loans in another blockchain dollar, USDC. We'll refer to these as Compound USDC bonds. As Buterin points out later on in the thread, the rate on Compound USDC bonds is 6.5%, quite a bit lower than Compound DAI bonds.

What might explain this discrepancy?

Not credit risk, since in both instances the same creditor—Compound—is responsible for creating the bonds. Which leaves varying levels of collapse risk as an explanation. USDC is a regulated stablecoin (i.e. it has the government's approval). DAI isn't. And USDC has genuine U.S. dollars backing it, whereas DAI is backed by highly volatile cryptocurrencies. So the odds of USDC collapsing are surely lower than DAI.

How much interest do USDC bond holders require to compensate them for collapse risk? Assuming that Compound's risk of failing is worth 5.5% of interest (as we already claimed), that leaves just 1% attributable to the risk of USDC failing (6.5%-5.5%). Put differently, investors in Compound USDC bonds will require 5.5% and 1.0% to compensate for credit risk and collapse risk respectively, for a total of 6.5%.

Oddly, the yield on a Compound USCD bond is less than the hypothetical yield on our safe Treasury DAI bond (6.5% vs 7.0%). Why is that? Even though Compound is riskier to lend to than the Treasury, a DAI-linked return is riskier than a USDC return. Another way to think about this is that if the Treasury were to also issue USDC bonds, those bond would only yield 2.5%. To account for credit (and other) risks investors would require a base 1.5% with an extra 1.0% on top for the risk of USDC breaking.

The convenience yield

Let's bring in one last layer. Something called the convenience yield is lurking behind this.

When you lend me some tokens, you need to be compensated for more than just credit risk i.e. the risk that I won't pay back the tokens. You are also doing without the convenience of these tokens for a period of time. The replacement, my IOU, won't be very handy. For instance, the convenience of a dollar bill can be though of as the ability to mobilize it whenever you need to meet some pressing need. But if you've lent a $100 bill to me then you've given up all that bill's usefulness. Instead, you're stuck with my awkward $100 IOU. You need some compensation for this. (Unconvinced? Head over to Steve Randy Waldman's classic ode to the convenience yield).

So when we break down the components of the interest rate on DAI bonds, there must be some compensation required for forgoing the convenience of DAI, its convenience yield. Earlier I attributed the big gap between rates on Compound DAI and USDC bonds to varying odds of each scheme failing. However, the gap could also be explained by varying convenience yields. If the convenience yield of a DAI token is higher than that of a USDC token, we'd expect an issuer of a DAI bond to pay a higher rate than on a USDC bond, in order to compensate DAI holders for giving up on those superior conveniences.

If DAI's convenience yield is higher than USDC's, what might explain this gap? DAI is completely decentralized and can't be monitored. USDC isn't. It is less censorship-resistant than DAI. So perhaps USDC just isn't as handy to have around.

So some of the 11.5% rate on Compound DAI bonds—say 2%—may be due to the convenience yield forgone on lent DAI. If DAI had the same features as USDC, and thus had a lower convenience yield, a Compound DAI bond might only yield 9.5% (11.5% - 2.0%). If so, the discrepancy between the Compound DAI and USDC bonds—9.5% vs 6.5%—wouldn't be as extreme.

Summing up, let's revisit Buterin's tweet:

If my line of thinking is right, the discrepancy is accounted for a messy mix of the higher risk of lending to Compound (3), the danger of DAI cracking (2), and whatever convenience yield one forgoes when one no longer has DAI on hand (4-other). And of course, Buterin's first option is right too. I'm assuming that people are rational and can easily buy and sell various assets. But the sorts of large institutional players who set market prices may not be operating in crypto markets.Lending DAI to Compound offers 11.5% annual interest. US 10 year treasuries offer 1.5%. Why the discrepancy?— Vitalik Non-giver of Ether (@VitalikButerin) August 23, 2019